Intrinsic, extraneous and germane cognitive load

The nature of intrinsic, extraneous and germane cognitive loads

It is useful to consider the various purposes to which cognitive load may be allocated. There are three purposes that have been identified in literature (Paas 2003). These are intrinsic cognitive load, extraneous cognitive load and germane cognitive load.

Intrinsic cognitive load is that which is given to cognitively attending to a body of content within mind. This is effectively being ‘conscious’ of the content. This will require holding each of the individual elements plus all interactivity between those elements.

Germane cognitive load has been described as that which is relevant to the task of “learning” the to-be-learnt information. It is germane to the learning process. This means, specifically, the modification of schemas in long term memory so that they come to account for the newly presented information.

Germane cognitive load will encompass deliberate consideration and reflection on how newly presented content relates to one’s current knowledge base. Personal queries may include identifying how the new content is the same, how it differs, whether it is a generalisation of already held schemas and thus needs to be integrated, or whether it is distinct to all current schemas and represents a “new” body of knowledge. In schemas theory this represents the distinction between assimilation (is similar to existing schemas) and accommodation (is distinct to existing schemas and so new schemas are required to accommodate it).

Extraneous cognitive load is that which is needed in order to attend to, process and enact the cognitive management of presented resources. Extraneous cognitive load results from the manner by which the to-be-learnt content is presented (the instructional materials and activities).

In more recent arguments Sweller (2010) has noted that the cognitive load imposed upon a learner may be either relevant or not relevant to the learning of the content. Intrinsic load and germane load are both relevant to learning. Extraneous cognitive load is not.

For the learning process to be effective learners will need to attend to the content elements, plus all aspects of their interactivity, plus how this relates to one’s current knowledge base, and responding appropriately cognitively to it.

Extraneous cognitive load impacts negatively upon learning and should be reduced whenever is practical.

Intrinsic cognitive load will derive from the learner’s mental representation of the to-be-learnt content and are germane to the learning process. By increasing the attentional processing given to how new information aligns and relates to existing schemas germane activities are amplified.

The additive relationship between intrinsic and extraneous cognitive loads

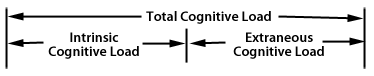

We will consider a model that handles intrinsic cognitive load and extraneous cognitive load. These are additive to define the total cognitive load experienced by a learner. This is demonstrated in the graphic below.

Intrinsic cognitive load

Intrinsic cognitive load is due to the intrinsic nature of some to-be-learned content. Intrinsic cognitive load cannot be modified by instructional design without altering the actual content that is to be learnt.

For example, content which is high in element interactivity remains high in element interactivity regardless of how it is presented. Intrinsic cognitive load can only be reduced by modifying the content itself to remove some of the content complexity, thus redefining the body of content being learnt.

Extraneous cognitive load

Extraneous cognitive load is due to the instructional materials used to present information to students and the activities that students are directed to engage in. Teaching materials addressing a concept such as continental drift, for example, will be more effective if it makes an appropriate use of a series of graphics demonstrating this process visually rather than just a text only presentation.

By altering the instructional materials presented to students, the level of extraneous cognitive load may be modified. Altering materials in a manner that results in lower levels of extraneous cognitive load may facilitate learning, due to the freeing of cognitive resources which can then be allocated to aspects that are germane to learning.

Demonstration

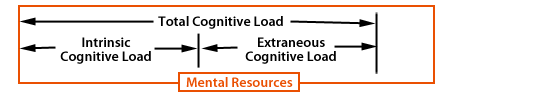

When intrinsic cognitive load is low (simple content) sufficient mental resources may remain to enable a learner to learn from "any" type of instructional material, even that which imposes a high level of extraneous cognitive load. Provided total cognitive load (the additive sum of intrinsic cognitive load and extraneous cognitive load) remains within the bounds of mental resources, learning should still be effective. Such a situation is displayed below.

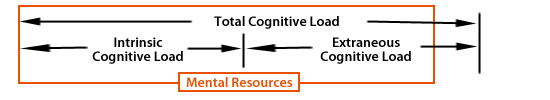

If the intrinsic cognitive load is high (difficult content, or rather, high element interactive content) and the extraneous cognitive load is also high, then total cognitive load may exceed mental resources and learning will fail to occur. Such a situation is displayed below.

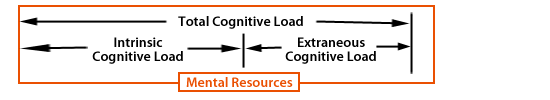

Modifying the instructional materials to engineer a lower level of extraneous cognitive load will facilitate learning if the resulting total cognitive load falls to a level that is within the bounds of mental resources, as displayed below.

In situations where the total cognitive load imposed is within the bounds of mental resources, learning may be further facilitated by increasing the intrinsic cognitive load. This may be achieved through instructional design strategies that increase germane activities by leveraging aspects of the learners evolving knowledge and skills (their schemas). Note, however, that this will only be effective in promoting learning if such engineering of increasing intrinsic cognitive load does not in and of itself result in an exceeding of mental resources.

Next: Problem solving with means-ends analysis

References

Paas, F., Tuovinen, J. E., Tabbers, H., & Van Gerven, P. W. M. (2003). Cognitive Load Measurement as a Means to Advance Cognitive Load Theory. Educational Psychologist, 38(1), 63–71. http://doi.org/10.1207/S15326985EP3801_8

Sweller, J. (2010). Element interactivity and intrinsic, extraneous, and germane cognitive load. Educational Psychology Review, 22, 123–138.